The Federal Reserve (Fed) has engineered a massive hawkish shift, causing a bit more stock market volatility recently. But how worried should investors be? Here we take a look back at historical performance for stocks before, after, and much after initial Fed rate hikes to help reassure any nervous investors out there. We also take a quick look at what the Fed pivot could mean for growth/value and large cap/small cap trends given the maturing business cycle.

Massive Hawkish Shift

With the recent pivot by Jay Powell and Company at the Fed, rate hikes have been getting a lot of attention. And rightly so, given the bond market has gone from pricing in one 2022 rate hike just a few months ago to now pricing in three to four. That’s one of the most dramatic hawkish shifts by the Fed in a short period of time that we’ve ever seen, so some market jitters are not surprising.

How Much Should We Worry?

A look back at history may help calm some investors’ jitters around the start of Fed rate hikes. As we wrote in our Outlook 2022: Passing the Baton, stocks tend to do well leading up to initial Fed rate hikes. There we highlighted the average 15% gain during the 12 months ahead of the initial hike of an economic cycle, including gains in all nine cases back more than 60 years. This makes sense given it takes a strengthening economy to create the job gains and inflation the Fed needs to see to take away the punchbowl. We see the first rate hike coming in either March or May, and with the S&P 500 Index up nearly 20% since March of 2021, and more than 10% since May 2021, those gains may already have occurred.

Looking beyond the initial hike, on our LPL Research blog last week we looked at how stocks performed during various periods after the Fed starts to hike rates. The story is similar, with the S&P 500 up an average of 7.5% six months later and 10.8% over the next 12 months historically. Stock were up all eight times one year after those initial hikes going back to the early 1980s. So based on history, the start of a rate hiking campaign by the Fed should not be too worrisome for investors.

Looking Out Longer Term

But what does the hike mean further out, say 2023 and beyond? In Outlook 2022, we noted that initial Fed rate hikes can help us mark where the economy is in its cycle. The start of rate hikes typically happens in the early-to-middle stages of the cycle, where stocks historically see solid gains as we are forecasting for 2022.

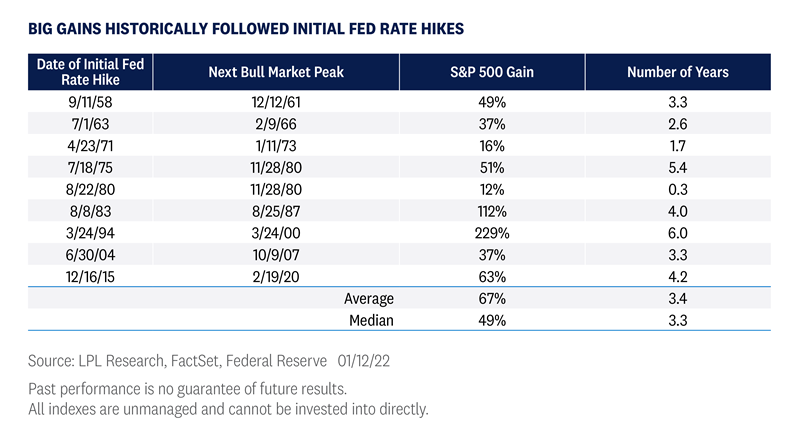

But we can extend this exercise further and look at how stocks have done from the initial rate hike of a cycle until the end of the accompanying bull market, as we have done in [Figure 1]. Those first rate hikes have been followed by an average gain of 67% before the subsequent bull market peak. For those keeping score at home, that would take the S&P 500 to over 7,700 (no, that is not a forecast) before the next 20% or more decline.

On average, after rate hikes start, bull markets have run for about three to four years (or 40 more months) before peaking, with the longest in the late 1990s at six years (72 months) between the 1994 hike and the bull market top in March of 2000.

We can also look at where in economic cycles these first rate hikes occurred based on the dates of the economic expansion. This can give us a rough idea of how much more economic growth we might expect after the Fed starts hiking rates.

This exercise reveals that, on average, expansions were 40% completed upon arrival of the Fed’s first hike. However, the August 1983 hike occurred only about one-quarter of the way through that expansion, which we think is more representative of how long this unusual cycle may last. We’re not even two years in and we think this cycle has a few more years left.

Implications For the Growth-Value Rotation

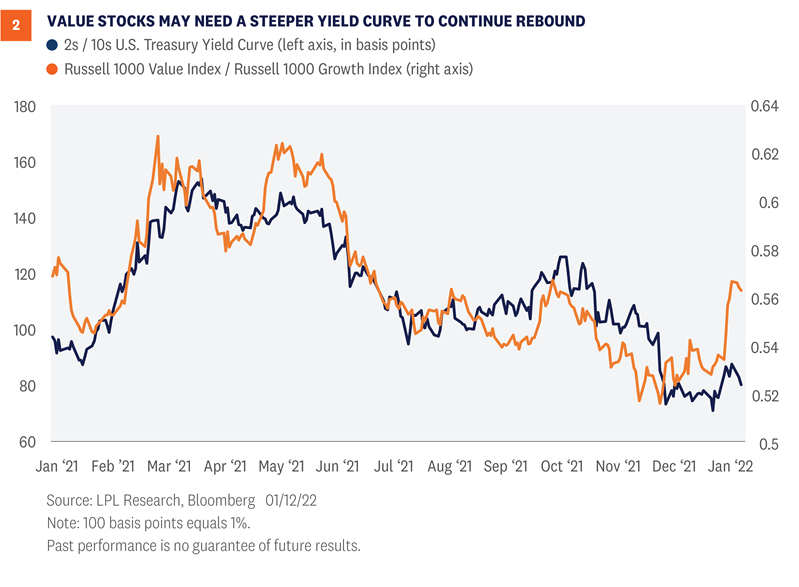

After growth stocks performed so well throughout much of the pandemic, value stocks have shown signs of life recently. Year to date the Russell 1000 Value Index has gained 1%, ahead of the more than 5% drop in the 1000 Growth Index. That follows about four percentage points of outperformance by value in December.

As shown in [Figure 2], the relative strength of value stocks has been closely tied to the yield curve, or the difference between 2-year and 10-year U.S. Treasury yields. A steeper yield curve tends to be good for financials, the biggest value sector, so this makes sense.

One of the reasons we squared up our views on the growth and value styles this month in our latest Global Portfolio Strategy report is because we think the opportunity for yield curve steepening may be somewhat limited now that the Fed pivot has occurred and the bond market is pricing in more than three rate hikes for 2022. If the 10-year yield doesn’t get much higher than 2% this year, as we expect, and the Fed follows through with a series of hikes and maintains its credibility as an effective inflation fighter, then the yield curve may actually flatten.

We are not worried about an inverted yield curve signaling recession, but we are skeptical that value stocks will continue to outperform at such a strong pace for much longer even with support from strong, though slower, economic growth and a likely further rise in interest rates.

Scales May Be Tilting Toward Large Caps

Small cap stocks have historically done better early in economic expansions, so as this cycle matures, large caps may have an edge. While we do not fear an impending recession, we do believe tighter monetary policy marks the economy’s progress toward mid-cycle. As such, we have become a bit less enamored with small caps, taking our view down from positive to neutral this month.

While small caps have historically performed well in inflationary environments, this cycle is unique and we believe larger companies are better positioned for the current environment of supply chain challenges and labor shortages (where a big chunk of the inflation is coming from). In addition, weakness in biotech and other more speculative, richly valued pockets of the market, should it continue, will make it difficult for smaller cap stocks to keep up with their mostly higher quality, better-resourced large cap peers.

Conclusion

The Fed has engineered a massive hawkish pivot, contributing to an increase in volatility recently. But a look back at history provides some reassurance, as stocks have historically performed well leading up to and after the first rate hike of a cycle, with significant upside before eventual bull market tops. Bottom line, even with rate hikes coming soon, we think this economic cycle and bull market have quite a bit left in the tank.

Jeffrey Buchbinder, CFA, Equity Strategist, LPL Financial

Ryan Detrick, CMT, Chief Market Strategist, LPL Financial

______________________________________________________________________________________________

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material is for general information only and is not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. There is no assurance that the views or strategies discussed are suitable for all investors or will yield positive outcomes. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Any economic forecasts set forth may not develop as predicted and are subject to change.

References to markets, asset classes, and sectors are generally regarding the corresponding market index. Indexes are unmanaged statistical composites and cannot be invested into directly. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any investment and does not reflect fees, expenses, or sales charges. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results.

Any company names noted herein are for educational purposes only and not an indication of trading intent or a solicitation of their products or services. LPL Financial doesn’t provide research on individual equities.

All information is believed to be from reliable sources; however, LPL Financial makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy.

U.S. Treasuries may be considered “safe haven” investments but do carry some degree of risk including interest rate, credit, and market risk. Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P500) is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

The PE ratio (price-to-earnings ratio) is a measure of the price paid for a share relative to the annual net income or profit earned by the firm per share. It is a financial ratio used for valuation: a higher PE ratio means that investors are paying more for each unit of net income, so the stock is more expensive compared to one with lower PE ratio.

Earnings per share (EPS) is the portion of a company’s profit allocated to each outstanding share of common stock. EPS serves as an indicator of a company’s profitability. Earnings per share is generally considered to be the single most important variable in determining a share’s price. It is also a major component used to calculate the price-to-earnings valuation ratio.

All index data from FactSet.

This research material has been prepared by LPL Financial LLC.

Securities and advisory services offered through LPL Financial (LPL), a registered investment advisor and broker-dealer (member FINRA/SIPC). Insurance products are offered through LPL or its licensed affiliates. To the extent you are receiving investment advice from a separately registered independent investment advisor that is not an LPL affiliate, please note LPL makes no representation with respect to such entity.

Not Insured by FDIC/NCUA or Any Other Government Agency | Not Bank/Credit Union Guaranteed | Not Bank/Credit Union Deposits or Obligations | May Lose Value